A Simple Story About Gelatin: Where It Came From and What It’s Made Of

I’ve always found it interesting how something as soft and quiet as gelatin has such a long and rich past. It goes all the way back to ancient Egypt. Back then, people didn’t use it in food—they used it as glue. That might sound odd today, but it worked for what they needed.

Fast forward to the year 1690 in the Netherlands—that’s when gelatin was first made in a factory. Later, in the 1600s, Britain turned gelatin-making into a big industry. By the 1700s, countries like France, the U.S., and Germany were also producing gelatin in large amounts. And believe it or not, we’re still doing it the same way today, just with better tools.

Before the 18th century, people mostly used gelatin to help make leather. But things started to change in 1814, when British scientists figured out how to make something called ossein, which comes from bones. That kicked off the large-scale production of gelatin. Around the same time, edible gelatin was also beginning to be made—yes, the kind that goes into your jelly or gummy bear.

In the second half of the 1800s, people found that gelatin could be used in photography. That discovery helped the industry grow even more. But in Japan, things moved a little slower. Gelatin didn’t really take off there until the 19th century. One reason is that Japan already had agar, which is made from seaweed and works in a similar way for food. Still, after World War II, as Japan’s diet started to include more Western foods, people began using more gelatin. Both the demand and production increased year after year.

By the way, the word “gelatin” comes from the Latin word gelatus, which means hard or frozen. People started using it widely around the early 1700s. It fits, doesn’t it?

Where Gelatin Goes Today

Nowadays, gelatin is used in four big areas: food, medicine, photography, and industry. The world makes about 300,000 tons of it every year.

Let me break it down:

- About 70% goes into food.

- Around 20% is used in medicines.

- The last 10% covers things like photography and industrial uses.

If we look at where it’s made and used around the world:

- Europe leads the market, with about 40% of total use.

- North America follows with 20%.

- Asia and Oceania together use about 20%.

- South America takes around 17%.

In Japan, according to a report from 2005, about 15,000 tons of gelatin were sold that year. Of that:

- 60% was used in food.

- 20% went into photography.

- 15% for medicine.

- 10% for industrial products.

What Gelatin Is Used For

Let me show you some common uses. You’ve probably come across gelatin without even knowing it.

In Food:

You’ll find it in:

- Jelly

- Marshmallows

- Gummy candies

- Puddings

- Pressed candy

- Yogurt

- Ice cream

- Side dishes and soups

- As a binder in ham and sausage

- To clarify wine

In Medicine:

It’s used to make:

- Hard and soft capsules

- Microcapsules

- Medical tapes

- Tablets and lozenges

- Suppositories

- Hemostatic agents (used to stop bleeding)

In Photography:

Gelatin is key in:

- Photographic film

- X-ray sheets

- Photographic paper

- Printing materials

In Industry:

It also works as glue for:

- Musical instruments

- Sandpaper

- Matches

…and more.

What Gelatin Is Made From

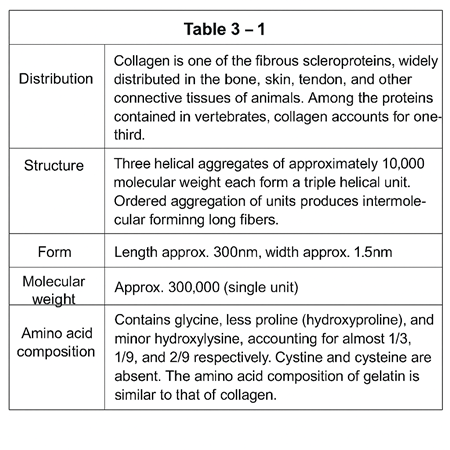

So what’s inside gelatin? It’s all about a protein called collagen.

Gelatin is made mostly from cow bones, cow hides, and pig skins. Around the world, the breakdown of raw materials looks like this:

- 70% from pig or cow skin

- 30% from cow bones

These parts of the animal are rich in collagen. But collagen is tough stuff. It doesn’t dissolve easily. So before it becomes gelatin, the raw materials go through a process.

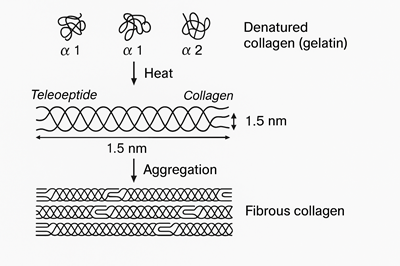

First, they are treated with either acid or alkali—this helps break them down. Then they’re heated. This heat breaks the triple-helix shape of collagen (think of a twisted rope). That rope then splits into smaller, random strands.

After this heat treatment, collagen turns from something that doesn’t mix well with water… into something that dissolves easily—gelatin.

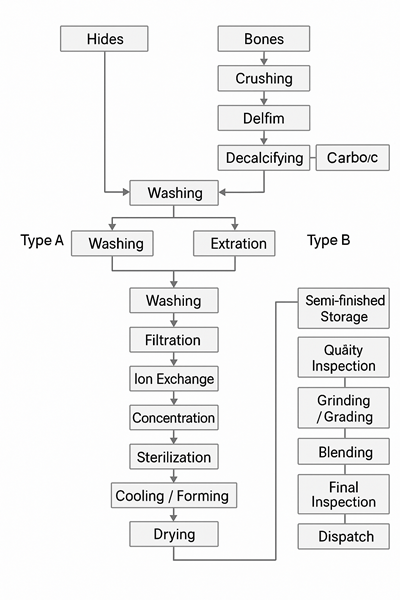

How Gelatin Is Made – A Step-by-Step View

1. Raw Materials and Pretreatment

It all starts with animal materials. Most of the time, we use cow bones, cow hides, and pig skins.

For cow bones, there’s a special step first. Bones are made up of a lot of minerals—about 75% of them are things like calcium phosphate. To get rid of those minerals, the bones are soaked in diluted hydrochloric acid. After that, what’s left is mostly collagen, and we call it ossein.

To get the best-quality gelatin from these materials, we have to pre-treat them. There are two ways to do this:

Acid treatment (Type A): uses acids like hydrochloric or sulfuric acid. This process usually takes a few hours to a few days.

Alkali treatment (Type B): uses lime (a kind of alkaline material) and takes much longer—about 2 to 3 months.

Which method is used depends on the raw material and the desired properties of the final gelatin.

2. Washing and Extraction

After pretreatment, we rinse the material thoroughly to wash away any leftover acid or alkali.

Then comes the extraction step. We heat the material gently using warm water—usually around 50 to 60°C (122 to 140°F)—to pull out the gelatin. This is called the first extraction.

But we don’t stop there. The leftover material still holds more gelatin. So we heat it again, this time with hotter water, to do a second extraction. Sometimes, this process is repeated several times.

This way, we get as much gelatin as possible.

3. Purification

Now we have a gelatin-rich liquid. But it’s still not ready. It contains impurities and needs to be cleaned up.

So, the gelatin solution goes through filters and sometimes ion exchange systems. These steps help remove unwanted substances and raise the purity of the gelatin.

4. Concentration and Drying

Once it’s clean, the gelatin liquid is concentrated to thicken it. We also sterilize it at this stage to kill any germs.

After that, the warm gelatin is cooled until it forms long, jelly-like strips. These jelly strips are then air-dried under controlled room conditions—usually with ventilation and air conditioning to keep the environment just right.

This turns the gelatin into a dry, solid form.

5. Final Processing and Quality Testing

The dried gelatin isn’t packed right away. First, we test its physical and chemical properties—things like gel strength, moisture level, and clarity.

If the gelatin passes all tests, it’s crushed into powder, sifted, and then blended with other batches to make sure everything is consistent. Finally, it’s packaged according to the form customers need—whether that’s powder, sheets, or granules.

Before any product leaves the factory, it goes through a final inspection. Only if it passes everything does it get shipped out.

Summary: The Gelatin Production Flow

Here’s a quick recap of the five steps:

Pretreatment

Cow bones are demineralized with acid to make ossein.

Pig skins and cow hides are treated with acid (Type A) or lime (Type B).

Washing & Extraction

Rinse off leftover chemicals.

Extract gelatin with warm water in multiple rounds.

Purification

Filter and clean the gelatin liquid to remove impurities.

Concentration & Drying

Thicken and sterilize the solution.

Cool it into jelly strips and dry them in a controlled room.

Final Testing & Packaging

Test the semi-finished product.

Grind, sift, blend, and pack the final product.

Approve and ship after final inspection.

Let’s Talk About Its Main Features

1. Chemical Composition

Gelatin is a protein that comes from collagen, which we get from animals.

After going through several rounds of cleaning and processing, the protein content in gelatin is really high—usually over 85%. It also contains:

- About 8% to 14% water

- Around 2% ash (which is just a small amount of leftover minerals)

- Less than 1% fat and sugars

In short, gelatin is mostly pure protein. That’s part of what makes it so useful in both food and non-food products.

2. Amino Acid Composition

Since gelatin comes from collagen that’s been heated and broken down, their amino acid profiles are almost the same.

But there are two types of gelatin—Type A and Type B—and they do have slight differences:

- Type B gelatin (often made from bones) has a bit more hydroxyproline

- Type A gelatin (usually from pig skin) tends to have more tyrosine

Here’s something that surprised me: glycine makes up about one-third of all amino acids in gelatin. Even more interesting—every third amino acid in the chain is glycine. That’s a lot.

Why does this matter? Glycine is small and simple, which means it doesn’t take up much space. This allows the protein chains to pack tightly together. That’s a big reason why gelatin can form a gel.

Another important group of amino acids in gelatin are called imino acids—mainly proline and hydroxyproline. These two account for about 2 out of every 9 amino acids.

These imino acids have a special ring structure (a pyrrolidine ring, if you’re curious). Unlike glycine, they’re bulky and tend to “lock” the protein chain into place. This helps stabilize the spiral structure when gelatin sets.

3. What About Essential Amino Acids?

If you’re thinking about nutrition, you might wonder about the essential amino acids in gelatin.

Here’s what I found:

- Gelatin is high in lysine, which is good.

- But it has zero tryptophan—and that’s a problem if you’re using gelatin as your main protein source.

Because of that missing piece, gelatin is considered a limited protein from a nutrition point of view. It’s great for many things, but not a complete source of dietary protein on its own.

Gelatin Is Full of Polar Amino Acids

About 35% of the amino acids in gelatin have polar side chains. That means they can react with water and carry a charge. These polar groups include:

- Hydroxyl groups (about 15%)

- Acidic groups (about 12%)

- Basic groups (about 8%)

This matters because these side chains affect how gelatin behaves in different environments—especially in liquids.

What Happens During Gelatin Production

Now, let’s back up a bit.

In natural collagen (before it becomes gelatin), some amino acids like aspartic acid and glutamic acid go through a change called amidation. This gives collagen a high isoelectric point (that’s the pH where it has no net charge), usually around pH 9 to 9.2.

But during gelatin production, something interesting happens. These amide groups break down—they hydrolyze, releasing ammonia and turning into carboxylic acid groups. This chemical change lowers the isoelectric point of the resulting gelatin.

Type A vs. Type B Gelatin

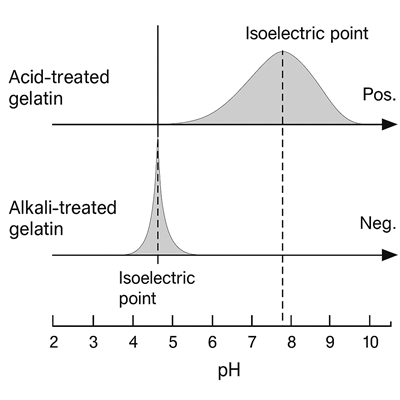

This is where the two types of gelatin behave differently:

- Type B gelatin (the one made through alkaline or lime treatment) goes through almost complete deamidation. That drops its isoelectric point down to around pH 5.

- Type A gelatin (made with acid treatment) has a shorter processing time, so the deamidation is only partial. Its isoelectric point stays higher, between pH 8 and 9, more like collagen.

I found this fascinating: Type A gelatin ends up with a broader range of isoelectric points because different molecules go through different amounts of deamidation. But Type B gelatin has a more narrow and consistent range.

How Gelatin’s Charge Changes with pH

So, why does this matter?

Because in water, gelatin’s charge changes with the pH of the solution:

- Below its isoelectric point, gelatin molecules are positively charged.

- Above that point, they’re negatively charged.

This affects everything from viscosity to how clear the solution is. For example, if you mix gelatin with an electrolyte that has the opposite charge, it could form a cloudy solution. That’s why, when using gelatin in formulas, I always make sure to check the pH.

Bottom Line

The isoelectric point of gelatin depends on how much deamidation happened during processing:

- Alkaline-treated (Type B) gelatin = Lower isoelectric point (~pH 5)

- Acid-treated (Type A) gelatin = Higher isoelectric point (pH 8–9) with more variability

In real-world use, that means gelatin’s behavior—like how thick it is or how clear it stays—can change based on how acidic or basic the environment is.

What About Gelatin’s Molecular Size?

One thing I didn’t realize at first is that gelatin isn’t just made up of one simple kind of molecule. In fact, it’s a mix of many different sizes. Let me break this down in a way that’s easy to follow.

Gelatin Comes from Big Protein Chains

Gelatin starts off as collagen, which is a strong, structured protein found in animals. Collagen itself is made up of three long chains—we call them alpha chains (α-chains)—each with a molecular weight of about 100,000 daltons.

When we heat collagen to make gelatin, those tightly packed chains unwind and separate.

But it doesn’t stop there.

During production, some of these α-chains bond together to form:

- β-chains (dimers) – two α-chains linked

- γ-chains (trimers) – three α-chains linked

So, when we talk about gelatin, we’re really talking about a mixture of these different components.

Why Gelatin Has Different Sizes

Depending on the raw materials used and how the production is done—like how long it’s treated or how hot the process gets—some of the protein chains get randomly cut.

That’s why gelatin isn’t made up of one single size of molecule.

Instead, it’s a whole range of molecules, from tens of thousands all the way up to several million daltons.

That range of molecular weight affects things like:

- How gelatin dissolves

- How strong the gel will be

- Its clarity and stickiness

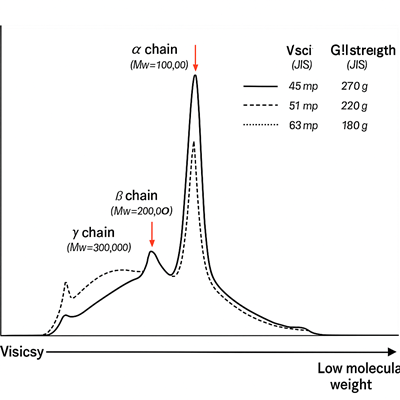

A Closer Look at Bone Gelatin

I once looked at a chart made using something called GPC (Gel Permeation Chromatography). It’s a way to separate and measure the sizes of molecules in a sample.

In one test of alkaline-treated bone gelatin, the chart showed a clear peak at about 100,000 daltons—that’s the α-chain showing up strong.

The chart also showed smaller amounts of:

- β-chains (around 200,000 daltons)

- γ-chains (around 300,000 daltons)

- and fragments with lower molecular weights

What It Means for Quality

The ratio of α, β, and γ components—and how wide the size range is—tells us a lot.

It reflects:

- The type of gelatin (acid- vs alkali-treated)

- The quality and grade of the product

- And even how experienced the manufacturer is

In general, high-grade gelatin will have a more consistent molecular weight distribution and fewer unwanted fragments.

What About Gelatin’s Molecular Size?

One thing I didn’t realize at first is that gelatin isn’t just made up of one simple kind of molecule. In fact, it’s a mix of many different sizes. Let me break this down in a way that’s easy to follow.

Gelatin Comes from Big Protein Chains

Gelatin starts off as collagen, which is a strong, structured protein found in animals. Collagen itself is made up of three long chains—we call them alpha chains (α-chains)—each with a molecular weight of about 100,000 daltons.

When we heat collagen to make gelatin, those tightly packed chains unwind and separate.

But it doesn’t stop there.

During production, some of these α-chains bond together to form:

- β-chains (dimers) – two α-chains linked

- γ-chains (trimers) – three α-chains linked

So, when we talk about gelatin, we’re really talking about a mixture of these different components.

Why Gelatin Has Different Sizes

Depending on the raw materials used and how the production is done—like how long it’s treated or how hot the process gets—some of the protein chains get randomly cut.

That’s why gelatin isn’t made up of one single size of molecule.

Instead, it’s a whole range of molecules, from tens of thousands all the way up to several million daltons.

That range of molecular weight affects things like:

- How gelatin dissolves

- How strong the gel will be

- Its clarity and stickiness

A Closer Look at Bone Gelatin

I once looked at a chart made using something called GPC (Gel Permeation Chromatography). It’s a way to separate and measure the sizes of molecules in a sample.

In one test of alkaline-treated bone gelatin, the chart showed a clear peak at about 100,000 daltons—that’s the α-chain showing up strong.

The chart also showed smaller amounts of:

- β-chains (around 200,000 daltons)

- γ-chains (around 300,000 daltons)

- and fragments with lower molecular weights

What It Means for Quality

The ratio of α, β, and γ components—and how wide the size range is—tells us a lot.

It reflects:

- The type of gelatin (acid- vs alkali-treated)

- The quality and grade of the product

- And even how experienced the manufacturer is

In general, high-grade gelatin will have a more consistent molecular weight distribution and fewer unwanted fragments.

Where to buy gelatin?

Send Your Inquiry Today